Family: Apidae

Subfamily: Apinae

Tribe: Apini Latreille, 1802

Genus: Apis Linnaeus, 1758

Subgenus: Apis (Micrapis) Ashmead, 1904

Species: Apis florea Fabricius, 1787

Common name: red dwarf honey bee

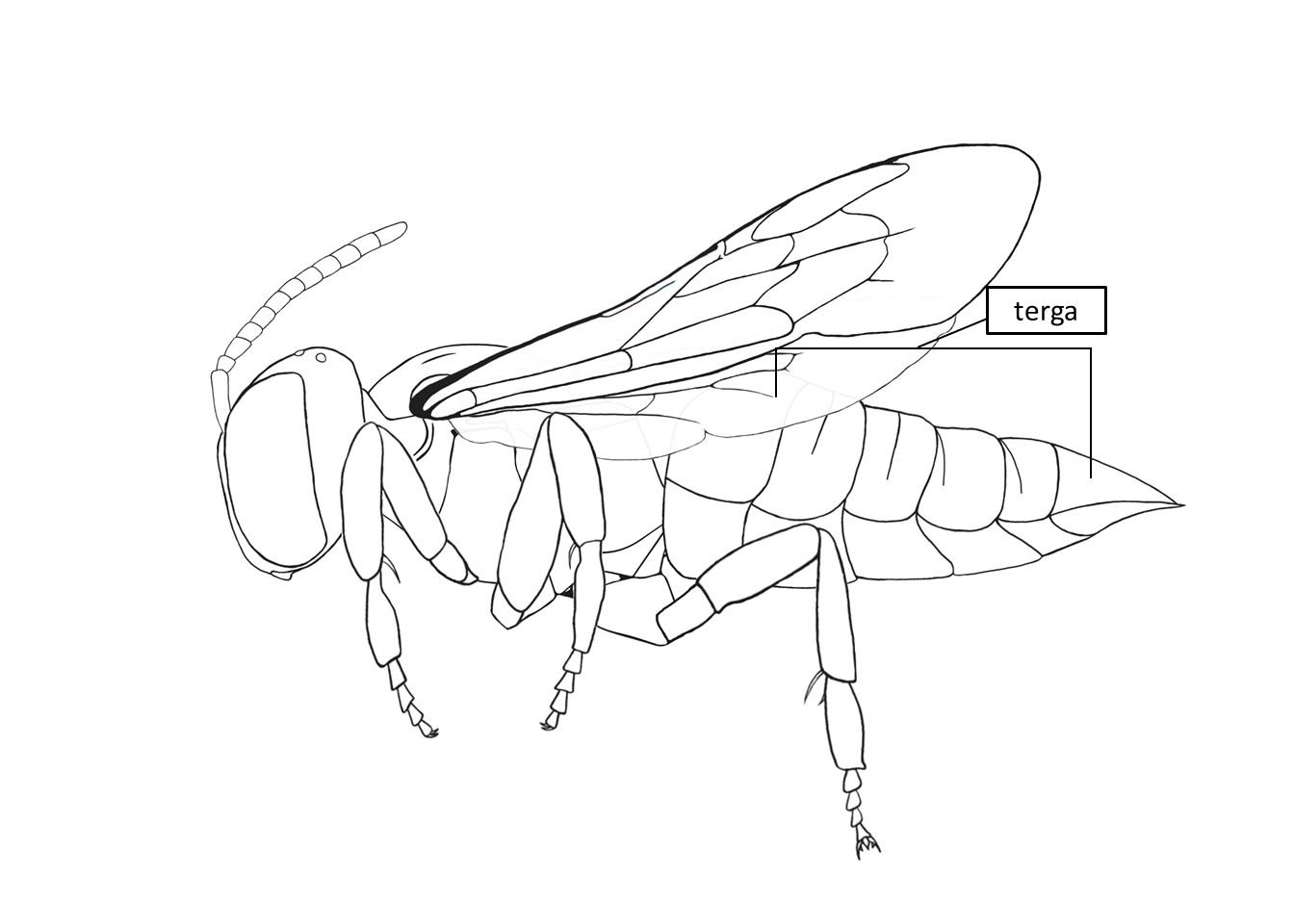

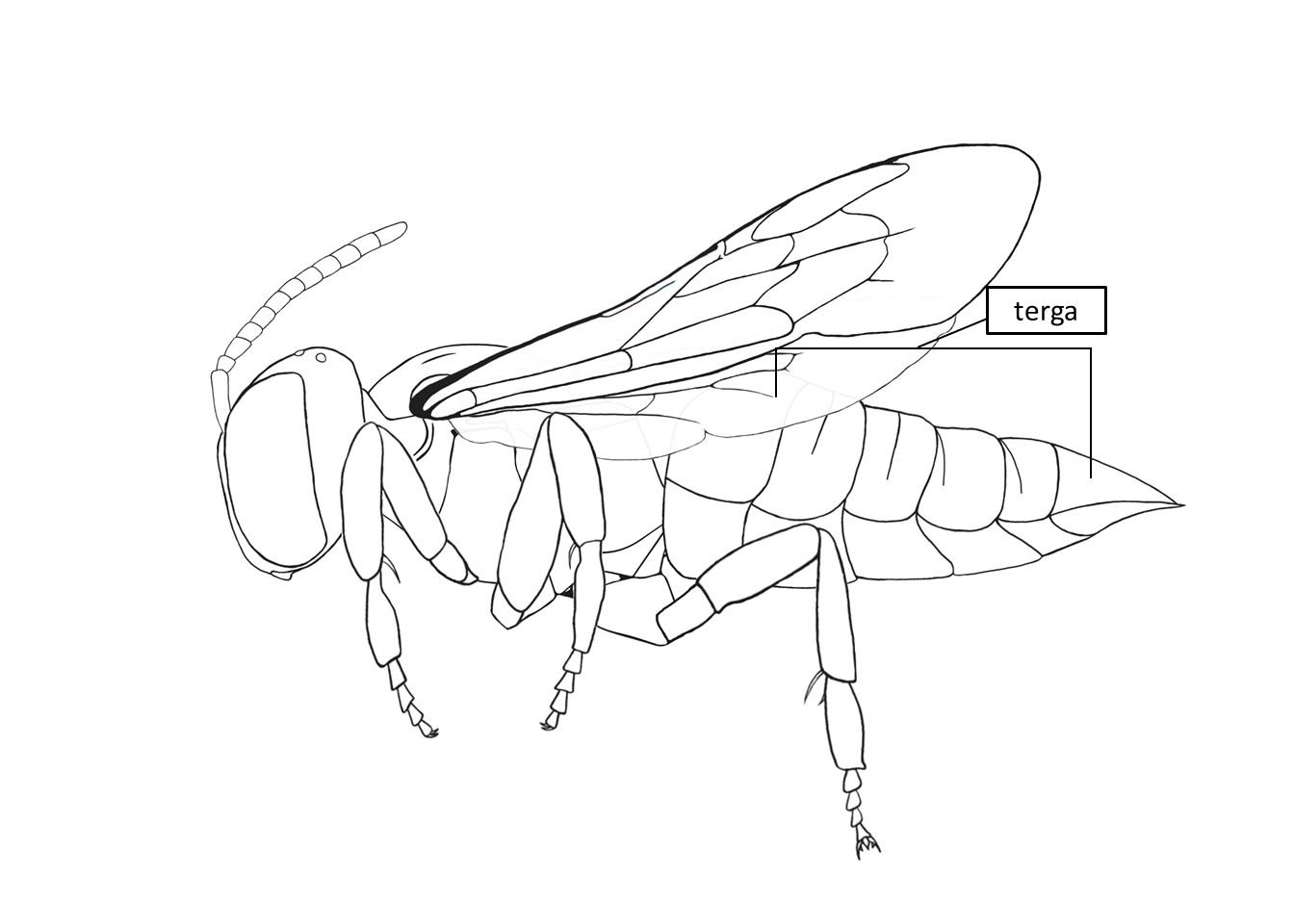

Apis florea is commonly known as the red dwarf honey bee. This species is among the smallest honey bees (body length of 7–10 mm, forewing length close to 6.8 mm), and along with Apis andreniformis constitute the subgenus A. (Micrapis). Wongsiri, et al. (1996) listed all the differences among the two species in the subgenus (see also fact sheet for subgenus Apis (Micrapis)).

and T2T2:

and T2T2: reddish-orange to reddish-brown (Fig 3 and 9).

reddish-orange to reddish-brown (Fig 3 and 9).Nests of A. florea are exposed and made up of a single horizontal comb that is built around and attached to tree branches or other support. Nests are often shaded and built in thickets and are not uncommon around human settlements and manmade structures. In the wild, they tend to be found more often in savannah woodlands, forests, or disturbed areas (Engel 2012Engel 2012:

Engel M. S. 2012. The honey bees of Indonesia (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Treubia 39: 41ndash;49.).

Morphological analysis by Ruttner (1988) had shown some geographic variability among populations of A. florea that can be organized in three monoclusters: one found in Sri Lanka and southern India, one distributed in Iran, Oman, and Pakistan, and the third in Thailand.

More locally, in Iran, the analysis by Tahmasebi, et al. (2002) showed two monoclusters in a geographical continuum: a western group of larger bees at higher latitudes and a lower latitude group of smaller bees to the east.

A multivariate analysis by Chaiyawong, et al. (2004) for populations of Thailand also showed some variation; more recently Hepburn, et al. (2005) produced a more comprehensive morphometricmorphometric:

from the Greek: "morph," meaning "shape," and "metron," meaning "measurement." Different schools of morphometrics are characterized by what aspects of biological "form" they are concerned with, what they choose to measure, and what kinds of biostatistical questions they ask of the measurements once they are made; such as configurations of landmarks from whole organs or organisms analyzed by appropriately invariant biometric methods (covariances of taxon, size, etc.) and in order to answer biological questions. Another sort of morphometrics studies tissue sections, measures the densities of points and curves, and uses these patterns to answer questions about the random processes that may be controlling the placement of cellular structures. A third, the method of "allometry," measures sizes of separate organs and asks questions about their correlations with each other and with measures of total size. There are many others.</p

database that included data from Ruttner (1988), Tahmasebi, et al. (2002), Mogga and Ruttner (1988) and Chaiyawong, et al. (2004) with the aim of filling in the geographic gaps of previous studies. They provided morphometricmorphometric:

from the Greek: "morph," meaning "shape," and "metron," meaning "measurement." Different schools of morphometrics are characterized by what aspects of biological "form" they are concerned with, what they choose to measure, and what kinds of biostatistical questions they ask of the measurements once they are made; such as configurations of landmarks from whole organs or organisms analyzed by appropriately invariant biometric methods (covariances of taxon, size, etc.) and in order to answer biological questions. Another sort of morphometrics studies tissue sections, measures the densities of points and curves, and uses these patterns to answer questions about the random processes that may be controlling the placement of cellular structures. A third, the method of "allometry," measures sizes of separate organs and asks questions about their correlations with each other and with measures of total size. There are many others.</p

data for populations across the entire distribution range of A. florea.

This species invaded the African continent in the 1980s (Bezabih et al. 2014Bezabih et al. 2014:

Bezabih G., N. Adgaba, H.R. Hepburn, and C.W.W. Pirk. 2014. The territorial invasion of Apis florea in Africa. African Entomology 22 (4): 888ndash;890.) and has expanded its natural distribution in to the Arabian Peninsula and the Middle East (Hepburn et al. 2005Hepburn et al. 2005:

Hepburn, H.R., B. Radloff, G.W. Otis, S. Fuchs, L.R. Verma, T. Ken, T. Chaiyawong, G. Tahmaseb, R. Ebadi, and S. Wongsiri. 2005. Apis florea : morphometrics, classification and biogeography. Apidologie 36: 359ndash;376., Haddad et al. 2009Haddad et al. 2009:

Haddad, N. S. Fuchs, H.R. Hepburn, and S.E. Radloff. 2009. Apis florea in Jordan: source of the founder population. Apidologie 40: 508ndash;512.).

According to Hepburn, et al. (2005), A. florea extends 7000 km from its eastern-most extreme in Vietnam and southeastern China, across mainland Asia, along and below the southern flanks of the Himalayas, westwards to the Plateau of Iran, and southerly into Oman. This constitutes 70 degrees of longitude (40°–110° East) and nearly 30 degrees of latitude (6°–34° North). Variations in altitude range from sea level to about 2000 m. A. florea has also been introduced in historical times in Saudi Arabia and Sudan, and occurred on Java, Indonesia up until ~50 years ago.

Distribution map generated by Discover Life -- click on map for details, credits, and terms of use.