Family: Megachilidae

Subfamily: Megachilinae

Tribe: Megachilini

Genus: Schizomegachile Michener, 1965

Common name: none

The single species in this genus, Schizomegachile monstrosa, has a black integumentintegument:

a tough, protective outer layer

and sparse white hairs throughout its body (Houston 2018Houston 2018:

Houston, T.F. 2018. A guide to the native bees of Australia. CSIRO Publishing, Clayton Australia, 280 pp.). They range in body length from 17–22 mm (Michener 2007Michener 2007:

Michener, C.D. 2007. The Bees of the World (2nd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 953 pp.). Schizomegachile had previously been considered a subgenus of Megachile but was elevated to genus status by Gonzalez et al. (2019).

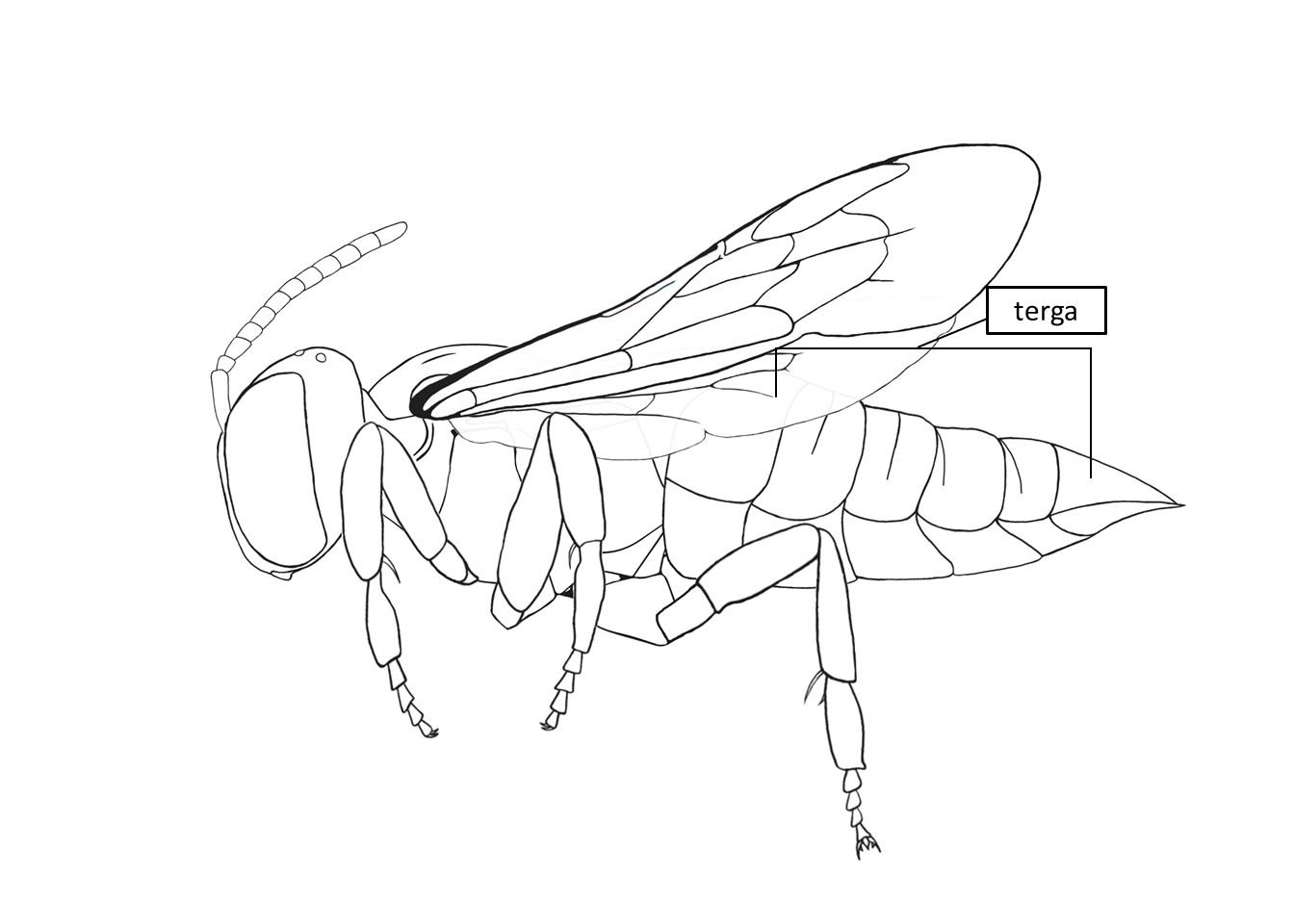

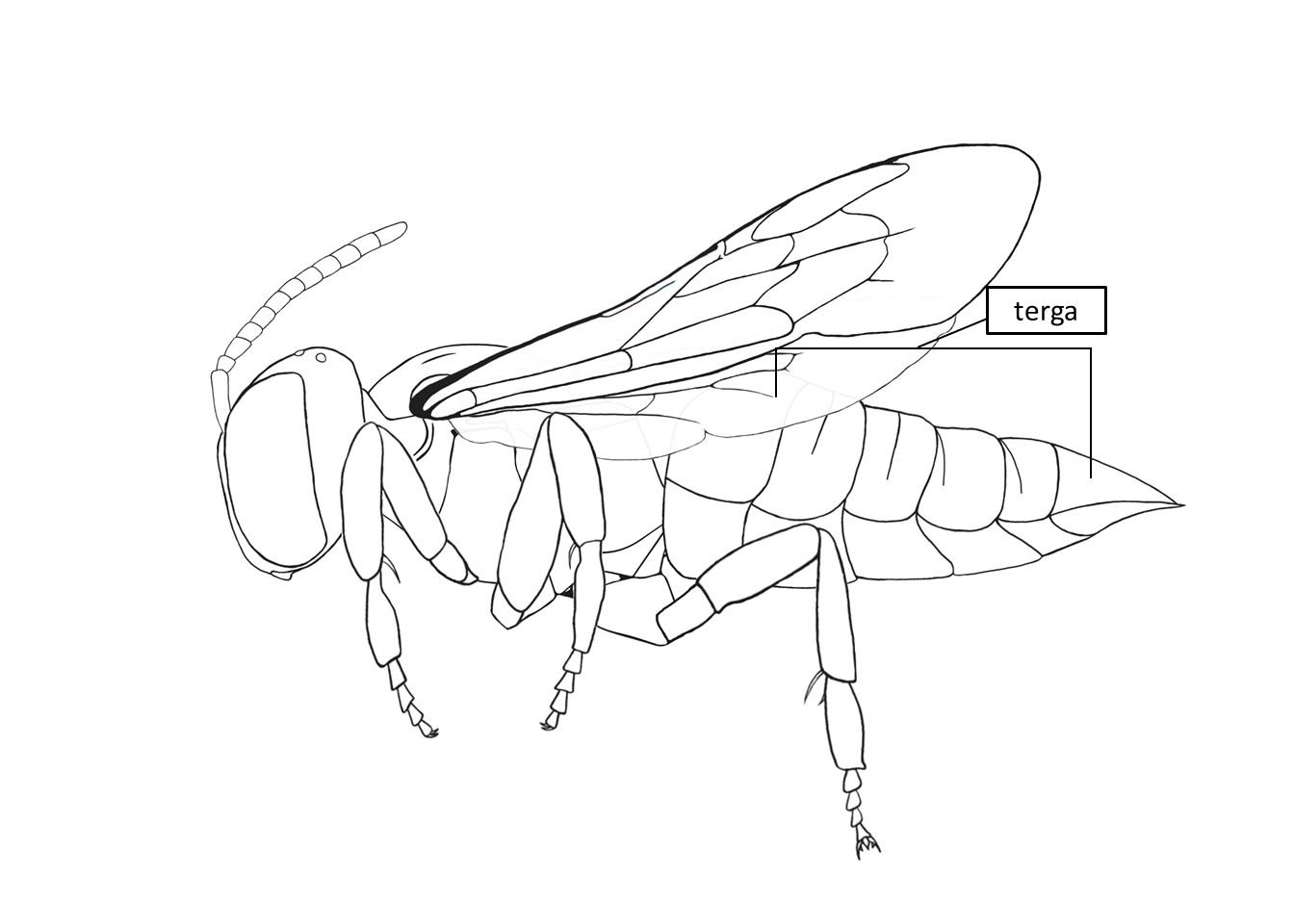

(modified from Michener 1965Michener 1965:

Michener, C.D. 1965. A classification of the bees of the Australian and South Pacific regions. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 130: 1-362.; Michener 2007Michener 2007:

Michener, C.D. 2007. The Bees of the World (2nd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 953 pp.)

with a median ridge.

with a median ridge. has a shiny, flat-topped longitudinal ridge.

has a shiny, flat-topped longitudinal ridge. is exposed, and less hairy and smoother than S3S3:

is exposed, and less hairy and smoother than S3S3: .

. divided by a broad median membranous region.

divided by a broad median membranous region.Schizomegachile may be confused with Hackeriapis as they have similar coloration, females share a similar mandiblemandible:

bee teeth, so to speak, usually crossed and folded in front of the mouth and clypeusclypeus:

a section of the face below the antennae, demarcated by the epistomal sutures shape, and the males of both groups have three exposed sternites (Michener 1965Michener 1965:

Michener, C.D. 1965. A classification of the bees of the Australian and South Pacific regions. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 130: 1-362.). However, Schizomegachile females have three-toothed tarsal claws and a projection on S6S6:

the plates on the underside of the abdomen, often abbreviated when referring to a specific segment to S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, or S8

(Michener 1965Michener 1965:

(Michener 1965Michener 1965:

Michener, C.D. 1965. A classification of the bees of the Australian and South Pacific regions. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 130: 1-362.). Schizomegachile males have bidentatebidentate:

having two teeth

mandibles, lack hind tibial spurs (and instead have an immovable spine), and do not have teeth on the apicalapical:

near or at the apex or end of any structure

margin of T6T6:

the segments on the top side of the abdomen, often abbreviated when referring to a specific segment to T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, T6, or T7 (Michener 1965Michener 1965:

(Michener 1965Michener 1965:

Michener, C.D. 1965. A classification of the bees of the Australian and South Pacific regions. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 130: 1-362.).

Schizomegachile are known to visit flowers of plants in the family Myrtaceae (Houston 2018Houston 2018:

Houston, T.F. 2018. A guide to the native bees of Australia. CSIRO Publishing, Clayton Australia, 280 pp.).

Schizomegachile nest in pre-existing cavities and have been observed nesting in bamboo trap nests (Houston 2018Houston 2018:

Houston, T.F. 2018. A guide to the native bees of Australia. CSIRO Publishing, Clayton Australia, 280 pp.). They use masticated plant material in the construction of their nests and partitions between nest cells (Houston 2018Houston 2018:

Houston, T.F. 2018. A guide to the native bees of Australia. CSIRO Publishing, Clayton Australia, 280 pp.).

Schizomegachile consists of one species, S. monstrosa (Michener 2007Michener 2007:

Michener, C.D. 2007. The Bees of the World (2nd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 953 pp.); this species is not known to occur in the U.S. or Canada.

There are no known invasives.

Schizomegachile occurs in the temperate regions of eastern and western Australia (Michener 2007Michener 2007:

Michener, C.D. 2007. The Bees of the World (2nd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 953 pp.).

Distribution map generated by Discover Life -- click on map for details, credits, and terms of use.

Gonzalez, V.H., G.T. Gustafson, and M.S. Engel. 2019. Morphological phylogeny of Megachilini and the evolution of leaf-cutter behavior in bees (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). Journal of Melittology (85): 1-123.

Houston, T.F. 2018. A guide to the native bees of Australia. CSIRO Publishing; 280 pp.

Michener, C.D. 1965. A classification of the bees of the Australian and South Pacific regions. Bulletin of the AMNH 130, 339 pp.

Michener, C.D. 2007. The Bees of the World (2nd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 953 pp.